VII

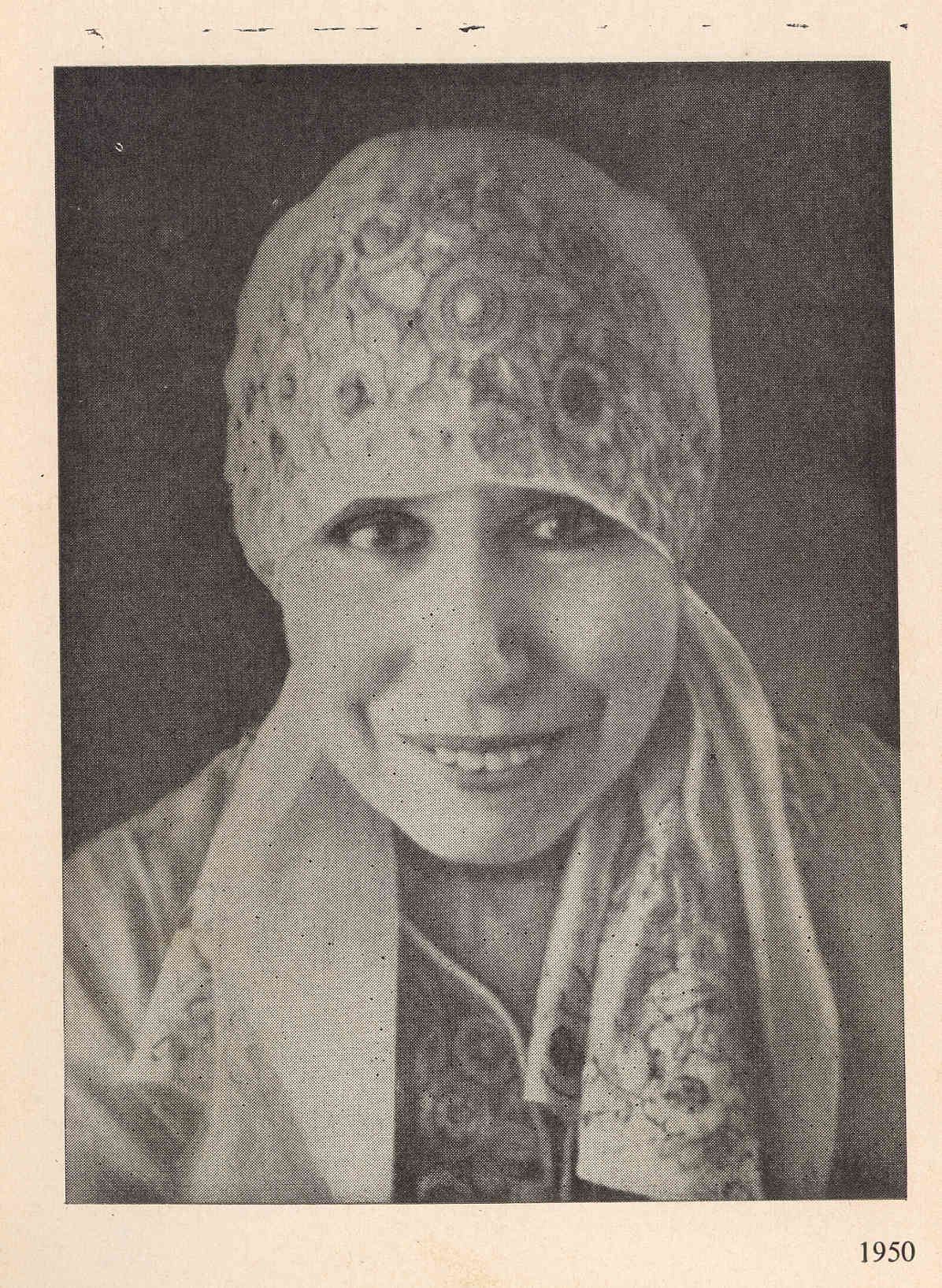

AFTER 1950 - NEW RELATION

1938-1950 was a long gap during which the story of my relation with the Mother has been told in Twelve Years with Sri Aurobindo. I need not repeat it here.

I could not sever my connection however, with the Dispensary all at once. When Sri Aurobindo's condition had taken a settled turn and our respective duties had been fixed, I began to attend to the patients during my off-duty hours. I used to give a verbal report to the Mother and Sri Aurobindo whenever there was any need for it. Fortunately after a few years Dr. Nripendra came up and took charge of the Dispensary. I was then relieved of the burden of running up and down and trying to maintain a precarious balance between my service to the Master and his disciples. My lodging was also shifted from the Dispensary to the Ashram Building.

Apart from this, since 1950, life followed a chequered course. I was thrown into an abyss, as it were, and enveloped in darkness. How I came out of it and, stepping up a long laborious path, found myself at the summit, alas, just for a short-lived Dawn - this

Page-54

will be the account of the following pages.

After Sri Aurobindo's passing, my occupation seemed to have gone. Champaklal had served both the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. So he could easily find his anchor fixed in the Mother. I had lost mine and had no other 'talent' with which to serve her. I had the fear that I would have to take a job elsewhere and would be shifted to my room below. With much trepidation I asked the Mother about my future, what I should do, where I should sleep, etc... Most spontaneously she replied, "Why? you will continue sleeping in Sri Aurobindo's room. As to work, you have a lot to do. You will work with Nolini on Sri Aurobindo's manuscripts." One single gesture swept away all my gloomy forebodings. What a divine solace it was! Somehow in spite of a thousand instances to the contrary, an image of the Mother as hard and strict had remained in the background of my consciousness. Even Sri Aurobindo's gentle admonition could not completely wipe ofi' the impression.

I quote another instance: in later years when my health suffered, I once said, giving lack of good sleep as one of the reasons, "There are lots of mosquitoes in Sri Aurobindo's room." The Mother asked, "Why don't you use a mosquitocurtain?" I was not prepared for this answer at all. For I thought rather childishly, that she would forbid any use of such a facility there. It would be a profane act! This human trait in the

Page-55

Mother and Sri Aurobindo, - simple commonsense in the Divine, was so reassuring!

My fears having been allayed and the sleeping problem resolved, the question of a place to work in had to be decided. Here too I feared lest the Mother should ask me to work in my own room downstairs, since there did not seem to be any place to spare. She put my anxiety at rest. She took a round of the eastern side of the house and coming near the small room facing the street, said, "You can work here." I was again speechless with wonder at her magnanimity. This room had been her sitting room before Sri Aurobindo's accident and so full of light and air, open to the blue sky and green trees that my poetic heart felt like 'dancing in glee' like Wordsworth's. In addition, I could have a view of the Mother through the long passage when she was meeting people in her room. Champaklal supplied me with a table used by Sri Aurobindo. Then I told the Mother that I had to work on the Savitri manuscript, type it and get it ready for publication. I don't remember if a typewriter was temporarily lent to me for the purpose, but the Mother said one day, "We have ordered a typewriter for you from Germany." When it arrived, she handed it to me, a brand new portable machine. I offered her my silent gratitude. The machine served faithfully for years, did many other jobs and is still being used for Sri Aurobindo's works.

Page-56

Sometime after Sri Aurobindo's passing somebody wrote an article on his last days and accused the doctors of giving him drugs against his consent. I complained to the Mother about this false charge. She said, "Why don't you write an article yourself?" I wrote a small brochure. The manuscript was read out to her. She not only liked it, but distributed it along with Amal's brochure The Passing of Sri Aurobindo to all the inmates. She was on the point of suggesting a title when I foolishly interrupted her and said that I had named it I am here, I am here. "Oh, then it is all right," she replied. This is how, impelled by her, I wrote my first prose work, published in May 1951. Then I thought of bringing out my correspondence with Sri Aurobindo in book-form. The Mother did not at first approve of the idea, she said that the letters were personal and meant for my use only. How could they be made a public property? When I replied that there were many letters which could be of general interest, she gave her consent. In fact she did not know what the contents of the letters were, for Sri Aurobindo had read out to her only those which had been of practical import. When I set myself to the task of compilation, I found the job not a little complicated and tedious. Fortunately, Albless, a Parsi disciple-friend who was living in the Ashram and was Amal's associate in editing Mother India, took up this work and helped me to publish the book. But he was of a

Page-57

puritan temperament and would not allow any flippant note or the playful swear words of Sri Aurobindo to see the light. Neither would he allow any of my weaknesses to be published, for that would lower the prestige of an 'old sadhak' in people's esteem! At times when there was a difference of opinion on some issues the Mother had to settle the matter.

There is still one long letter on Politics which Sri Aurobindo marked 'confidential'. The Mother did not allow it to be published. When this letter was privately shown to a well-known historian who while appreciating Sri Aurobindo as a great revolutionary, a great patriot, etc., etc., had passed the judgment that Sri Aurobindo had not the quality of leadership, it came as a revelation to him and he changed his views completely. In this letter, Sri Aurobindo chalked out item by item a plan of the political work he intended to carry out during leadership some of which he had already accomplished. It showed that Mahatma Gandhi had proceeded exactly on the lines envisaged by Sri Aurobindo, except that he made a fetish of passive resistance and non-violence.

Near about this time, I imagine, an idea flashed through my mind that I should write an account of our unique life lived together with Sri Aurobindo. But I rejected the idea at once, knowing that the Mother

Page-58

would not countenance it. At the same time, something seemed to push me to it and in a dubious frame of mind I drafted a few chapters; then the flame went out. It was long afterwards and in a different situation that the flame was rekindled and I obtained the Mother's permission. The story will be told in its proper place.

I had also written a long article in French on Sri Aurobindo as Guru, at the request of some French savants in Paris who were admirers of Sri Aurobindo. Naturally the article needed much pruning and a French friend helped me in this respect. It was read out to the Mother and she wrote on a small piece of paper, ' Tres bien' (very good) in appreciation.

This is the story of my literary work in the two decades.

In the year 1952 or 1953 we saw a few films on French writers and musicians like Balzac, Zola, and Chopin (originally a Polish Jew). I had some interesting talks with the Mother on them. I do not know how it happened. Probably because I had at that time become a teacher of French in the School and was therefore studying French literature, she wanted to help me in this respect. We saw two films on Zola; the first one was "J'accuse" (I Accuse). I still remember. When after seeing it she returned to the main Ashram Building, she said to me, "It is very interesting. You

Page-59

will see some people tomorrow whom I knew at that time. I was twenty then, i.e. in 1898." (She meant particularly Anatole France. She was very fond of him as a writer). Next day the second film was to be shown on Zola's life. I asked her in the morning: "Mother, have you read Zola?" "Not much'" she replied, "he is too pessimistic throughout. He looks at life exclusively from the exterior, it takes away all possibility of transformation. But from the literary point of view he is extremely powerful and very beautiful. The names of all his works were mentioned last night."

After some time, we had a film on Balzac, apropos of which I asked the Mother, "Have you read Balzac, Mother?" "Yes," she replied, "but I could never go to the end. His writing is so boring as if you are chewing stones. But from the psychological point of view, he is excellent; his observation of ancient customs, social habits, etc., is quite correct. If you want to read him for these things, he is very good, but for learning French he is not good at all; he has no style, his style is rocailleux [harsh]. His short stories are tolerable, but they are few.

"Zola has a better style and it is very powerful. What he has written is true; he is not a man of imagination, he is very concrete. I read a description of a garden - Paradou, I do not know in which book it

Page-60

is, it is magnificent. I have not read such a description anywhere else: so much wealth of splendour, harmony with Nature. When I went to the south of France, I saw such a garden. Reading him, I felt as if I was there in that garden. If you can find out that description, read it. It is worth reading."*

After this we saw the film on Chopin. The Mother asked me next day, "Were you there last evening ?"

"Yes, Mother," I replied and taking this opportunity, I asked, "Did you like the film?"

"No, I don't like Chopin's music; it makes me sick. His music is too vital."

"What about George Sand, Mother ?"

"She is like that; she is well-known for such things. She had many lovers and left one for another. Musset, I think, fared at her hands in the same way. But," she added with a smile "she was not so bad as all that" (as was depicted in. the film).

"Who was the other musician?"

"Oh, he is the famous musician, Lizt. It is he who made Chopin's success."

"Have you read Sand, Mother?"

"Oh yes, her novels are very interesting. She has written a lot. I have read most of it. She is an occultist. Her two books, La Croix Rouge and another

* Mother refers to a passage from the book "La Faute de l'Abbe Mouret" an English translation of which is given at the end of this section.

Page-61

one are occult." Then again with a smile she repeated, "She is not so hard!"

Now I am writing something which has no direct relation to my topic, except a chronological connection. I don't remember how it crept into my note-book. It concerns an Air Commodore who saw the Mother and had a talk with her. Since it bears on a general problem, I am putting it here. He said to the Mother, "I don't know at times what should be my course of action or my duty in the worldly life. Have I done the right thing? Was my attitude right? All these questions trouble me in spite of my best efforts to do the right thing. Where does one start?"

Mother: It is because you want to decide by the mind. The mind can never give the truth. Try to silence it and get the answer from within.

Visitor: For example, when I have a difference of opinion with my superior about the conduct of our subordinates?

Mother: There you must obey your superior, as you do in yoga. You may think differently from the Guru, but you must do what he says - that is what keeps you in the right attitude. It is not the action, but the inner attitude that matters most and decides finally your action. If you can't obey your Guru, you have to leave him. So also if in some vital matter you can't see eye to eye with your superior, you have no other alternative but to leave the job. Towards your

Page-62

subordinates, be as kind, generous and sympathetic as possible.

Visitor: To get the inner answer takes time.

Mother : Oh yes, it takes a lot of time, sometimes many years, and you have to go on patiently. Whenever you have a problem or some ideas of your religion to be followed or not, you have to see where they come from - from ancestors, social environment, education, etc., etc., and then dissociating yourself from all that, go within; feel here - in the heart.

* * *

*Paradou

A sea of green, in front, to the right, to the left, all over. A sea rolling its surge of leaves till the horizon, unchecked by impeding house or a piece of wall or a dusty road. A lonely, virgin, sacred sea spreading its savage softness into the innocence of solitude. Only the sun entered there, wallowed over the meadows in a golden sheet, ran through the alleys in the escaping course of his rays, let his flaming, fine hair hang through the trees, drank from the springs with a blond lip that sopped up the water with a thrill. Under a dust-haze of flames, the vast garden lived with the voluptuousness of a happy beast who has been let loose far away, away from all, free from all. Such debauchery of foliage, the swell of grass so overflowing

Page-63

that the garden seemed from one end to the other hidden, hailed, drowned. Nothing but green slopes and branches that gushed out like fountains, curly masses, curtains of forests hermetically pulled down, cloaks of creepers trailing on the earth, flights of giant branches swooping down on all sides.

With the passage of time, one could hardly recognize under this formidable invasion of sap the ancient outline of Paradou. In front, in a sort of an immense ring was to be found the parterre with its sinking ponds, its battered slopes, its worn out stairs, its fallen statues whose whitenesses were perceived at the bottom of the black lawns. Further away, behind the blue line of a sheet of water spread a jumble of fruit-trees. A little further down, an ancient forest thrust its violettish trunks streaked with light- a forest become virgin once again, a forest whose summits protruded like rounded hillocks unendingly, spots of yellow-green, green pale, puissant green in all its essences. T o the right, the forest was escalating the heights, planting little pine-woods, almost dying out in meagre bushes while bare rocks piled up an enormous rise - a collapsing mountain that obstructed the horizon; there ardent vegetation pierced through the earth, plants monstrous and immobile in the heat like reptiles in drowse; a silver net-a splash that from far resembled a dust of pearls-pointed to a water fall -the source of those tranquil waters that so indolently slid along the flower-bed. Finally to the left flowed the river in the middle of a vast prairie

Page-64

where it diverged into four streams and one witnessed their caprices below the reeds, between the willows, behind tall trees; plots of pasture extended the freshness of the low-lying terrains-a landscape bathed in a bluish mist, a morning-glade slowly melting away in the greening blue of the sunset. Paradou, parterre, forest, rocks and waters and meadows occupied the entire width of the sky.

*

The proper place for these two episodes was at the beginning of this chapter. But since I remembered them too late, they are inserted here.

Soon after Sri Aurobindo's passing in 1950, it was necessary to testify that the Mother had been all along in charge of the Ashram and that she still had the executive power. A document was drawn up and in front of a notaire of the town it was signed by a few members of the Ashram chosen by the Mother. I was one of the signatories.

A few months later, the Mother got prepared some gold rings with Sri Aurobindo's symbol engraved on the bevel and his small photo stuck inside. She herself put these rings on the fingers of the sadhaks selected by her. I was one of them. I remember very well the wonderful event. The Mother had come out of her bath-room in the morning, and standing in the passage she called for me. As I arrived, she caught hold of the third finger of my left hand and put the gold ring on it. I was so surprised that I could not utter a single word; I simply did pranam at her feet and came away.

But to my utter misfortune, after a number of years, I lost the ring. In fact it was my boy-servant who had stolen it. When I informed the Mother about it-I was seeing her then - she listened gravely and asked me how it had happend. To my proposal to call in the Police, she said, "No! that will invite a lot of troubles afterwards." The Mother never wanted to take the help of Police or of the law courts in any of our internal matters.

I cannot forget the loss of the doubly precious ring and lament sorely whenever I think of it.

Page-65

Fire-Baptism

At this time, i.e. between 1950 and 1952, in spite of my daily contact with the Mother, (in fact, for a long time afterwards) I was not quite free from moods of depression. During such moods I would go to the Samadhi. One day, as I was standing there, I saw the Mother looking at the Samadhi from a window in the corridor of the first floor. Almost immediately my head began to reel and I was obliged to sit down. The next day, I told her of this queer feeling. She said, "I know why. When you were standing there and looking towards me, I saw a dark cloud of depression coming from you in my direction. Naturally I had to react in order to protect myself. I pushed back the cloud. It went back to you and produced this sensation."

In the year 1953, the Mother fell ill and all our contacts with her stopped. When after a time the sadhaks resumed their contact I somehow did not do it. I would watch from near my office the Mother meeting people and giving them blessings. She could see me, but would not call me. I kept myself aloof waiting to be called. For, I had taken up an attitude like my friend Champaklal that I should not ask anything for myself. Things should come in their natural course. 1 do not know if this movement sprang from pride or humility. But throughout the rest of my

Page-66

life I have tried to follow this rule. Sometimes I doubted my sincerity and felt that I had lost much of the Mother's contact by sticking to a rigid attitude. Anyway, I had to wait pretty long before she called me and, though my attitude may have been right, I could not accept it with equanimity. Besides, Dr. Sanyal who had settled in the Ashram at this time had the Mother's touch everyday near my own office. He used to come in the morning and meditate in front of Sri Aurobindo's room at the east end. The Mother would come, making a shuffling sound with her Japanese sandals, and Sanyal would be ready to receive her. But the Mother, without ever looking at me, would walk straight to him and go back after blessing him. I would sit at a little distance, as a silent witness. As her apparent, but deliberate neglect would hurt my vanity, I would either move away or try to keep down my abhiman, teaching myself some samata.

This painful period continued for many months, till one day I entered again into her Presence. After finishing her usual distribution of flowers she suddenly cast a glance towards me and beckoned me. I simply rushed forward. With a broad smile she received me and blessed me with flowers. Since then my pranam continued and became a daily rite and worship till the next interruption. I do not know what had been prepared, what seeds had been sown in my inner field before I was called.

Page-67

On my birthday in 1953,

the Mother greeted me with her usual "Bonne Fete" and then

started in French, with a sweet smile, Quel age avez-vous .7 (how old

are you)?

Myself: 51 ans passe, Douce Mere. (51 years over, Sweet Mother).

Mother : Vous etes encore enfant (you are still a child). Then holding both my hands, she resumed in English : "You feel better now?"

Myself: Yes, Mother. I feel much better and stronger, but I can't get rid of the suggestion that I am getting on in age.

Mother: No, you must not listen to it. It is a collective suggestion thrown upon everybody. One can go on being active in spite of age. I have seen people of 90 who were younger than boys of 10. No, you must get rid of that suggestion altogether.

Myself: I don't feel at all that I am so old, but the suggestion is there. There are so many things left to be done.

Mother: Exactly. You must not allow that suggestion to disturb you. This year things are going to be hard for us. Difficulties will come to a head, I mean of things exterior. Even a small place like Pondicherry can be so hard, resistant.

Myself: Will there be physical trouble?

Page-68

Mother : Yes, even an attack on the organisation. It is then that one has to be firm in one's loyalty, endure in spite of all struggle and put one's will and faith on the side of the Divine. In 1956 on 23rd April something decisive will happen. 23rd April makes 2,3,4,5,6. That happens to be the date of Surendra Mohan's birthday; I remember that when he was here I told him about that date and his face at once changed. When he said it was his' birthday, I told him, "You must be here on that day." As I uttered 2,3,4,5,6, he got attracted; you know he is attracted by such things. Yes, it was he who sent some Bhrigu reading from Delhi, you remember, regarding Sri Aurobindo's departure and he was supposed to play an important part. Yes, it was a mantra to be repeated 10000 times. I wanted to have the mantra and repeat it myself, but he could not get it. I don't know why the man refused. At any rate I did not believe till the last moment that Sri Aurobindo was going to leave his body.* Afterwards it became clear to me what all

* Amal comments: "This is correct. On Dec. 3 she told me that Sri Aurobindo would soon read my articles. Later, when I asked her why she had let me go to Bombay on Dec. 3 she said that Sri Aurobindo's going had not been decided yet."

Page-69

the indications he had given meant. He was not pleased with his body. But you know how it happened. One day I told him, "You must think only of yourself, nothing else." He kept quiet for a while, then looked at me. There was such an intense sorrow in his eyes.

Myself: Do you envisage his coming back?

Mother: Well, he has himself said that he would come back in a supramental body, the first supramental body.

The other day I had an interesting dream. I saw that both he and myself had gone somewhere and were living in a house. He was very young with broad shoulders and a thin waist, as he always wanted to be. Only his eyes betrayed that he was Sri Aurobindo. I had my usual appearance - only younger, with the flowing hair ' of my early days. It was a rainy day; clothes had become damp. I wanted to bring out a blanket from his room. He was sleeping; the noise woke him and he said, "Why take all those old things again? Let us go out for a walk." He got up, put on his dhoti; I was in my robe de chambre. We walked on and came to a place near a hill. There was a big house near about on the other side of the hill. Both of us sat together on a lawn. After a while a young boy came out from nowhere, looked at us and went away. Then four or five people in charge of the Ashram came near, did not like

Page-70

our

sitting there and said, "Can't anyone say to these people that

they are spoiling our lawn?" They didn't dare to say it

themselves. Then Sri Aurobindo said, "Don't they know who we are

?" We wanted to see how the Ashram was getting on! It is not a

dream, but a vision, the place was far off, somewhere near Hyderabad,

and people dressed in the style there. This was the first time I saw

Sri Aurobindo so young. Well, what meaning it can have, I don't know

and when it will take place, shortly or after a millennium, I can't

say.

* * *

According to Champaklal Speaks, on the morning of 9th December 1953 after meditation, the Mother informed Dyuman that she would go up to her room in the top floor from that night. After that day she started spending the nights there. But now and then she would also spend some time there during the day. From March 20, 1962 onward, however, after going back to the room from the Balcony Darshan she did not come down at all.

Now, one early morning in 1954, I was urgently called by Pranab to see the Mother in her room. This was my first visit to the room. I saw her sitting on the sofa with her legs stretched out, the hair flowing down. It seemed she had fallen in the bathroom and injured her head. Pranab showed me the site of injury. I saw a tiny out near the crown, blood was oozing

Page-71

slowly, some hair was glued together due to clotting of the blood. The oozing was stopped by pressure and nothing farther seemed to be called for. Still, I felt that since it was a head injury, I had better call in Dr. Sanyal to share with me the divine responsibility. The Mother gave her consent. I found him still in bed. He heard the story, got up and quickly dressed himself. Both of us returned together. He examined the wound carefully and confirmed my observation. Pranab reminded me that the Mother strongly protested to the doctor's cutting the hair for the purpose of examining the wound. However while he was dressing the cut, she started talking with him, first of her health, then of sadhana. She said that as usual she had gone to the bathroom and was preparing a gargle with alum salt as she had some gum trouble, when she suddenly fell down. She said she had a floating kidney; it functioned well, though, and the body was receptive. Her nerves had been shattered in 1915, when she had gone back from here. Her condition had become very critical; she just managed to write a few lines to Sri Aurobindo, but though the letter did not reach him, she was cured by him. It took several months to build up the lost health.

During the subsequent periods in Pondicherry she was subjected to constant attacks by forces and formations. The fight was untiring especially between 3-5 am, when she used to work for the sadhaks and had

Page-72

to go out of her body. Just the time of getting up was the opportune moment for attack, because it was the most unguarded moment. That was how the accident happened. She seemed to have heard a voice, but did not obey it. She should have sat down. It was a case of black magic, according to her. She knew how the attack had come and who had made it, but she could not throw it back on the evil person.

"Why not punish such miscreants ?" asked Sanyal.

Mother: I don't believe in punishment.

Sanyal: Can't these forces be changed ? Mother: If they want; otherwise they suffer their fate. But they serve a purpose: they show your weak points in the body and you work on it. Transformation of the body is not easy. If it were not for this aim, I would have gone to Heaven long ago.

I had two visions : in one, while I was walking at 6 p. m. I saw children rushing to hear a humbug! I thought, what would happen in my absence! In the other, I saw an archbishop ; he was my late mother in disguise. We were in some house, closed on all sides. The archbishop was trying to convert me, but failed. Then I tried to leave the place, but found all the doors closed. This is a vision of things that are constantly going on inside us.

As regards the talk on sadhana, the only part I remember was that the Mother said she would not abandon Sanyal. She would even force down

Page-73

consciousness into him. I wished inwardly that she did the same thing for me as well, for the two doctors were similar in some respects. But surprisingly as soon as I formulated my desire, she addressing me, as if my thought had been communicated to her, said something I don't quite remember. We had many proofs of the Mother's sensitivity or thought-reading even from a distance.

After the work and the speech were over, we came down. The next morning, Sanyal came early and enquired if there was any news. I said that everything was quiet. Then he asked me what we should do. Probably the Mother would come down as usual. Should we ask her about her condition ? We decided, however, that both of us would stand in the passage through which she would go to the bathroom near by. Soon she came down, followed by Pranab, and silently passed by us. We also kept quiet, our question remained unuttered. Our conclusion was that she must be all right. This is the way of the Divine, I suppose.

Page-74